What Happened to Downtown Atlanta?

Downtown Atlanta was once a vibrant city center - now it's a hollow shell of it's former self. What caused it to be this way?

Published

Written by

Nathan Davenport

Downtown Atlanta, kind of sucks!

If you ever come to Atlanta, you’ll probably find yourself downtown for the tourist attractions we’re known for, like Georgia Aquarium, World of Coke, or the College Football Hall of Fame.

And you’ll take a stroll through Centennial Olympic Park fountains, ride the Ferris wheel, and if you’re lucky, end up having dinner from the Sundial!

But if you’re the type who likes to walk around your cities, you might start to feel a little bit well, awkward leaving dinner. Around 6 pm, Downtown starts to feel a bit empty, and maybe even creepy.

Introduction

Downtown today, the Downtown marketed towards tourists and travelers, is centrally a business, attraction district. Not many people live here permanently. The city starts to feel actively more hostile the later in the day you go.

Case in point, Olympic Centennial Park closes at sun fall, and bans the entrance of any soul who dares enjoy themselves in the center of Downtown. Back to your hotel room you go! Try not to get hit while crossing the street!

I’ve always thought this was strange. Downtown’s should be the jewel of the city, with activity happening at all hours of the day.

So I just want to know. Where is everyone in Atlanta? Why did this happen?

Background

I didn’t start to realize how under utilized our downtown is until traveling to some other cities, so i began to wonder: why don’t Atlantans care about their downtown? Is there a missed opportunity here?

Comparisons

Other city’s downtowns make Atlanta look, well to put it bluntly, embarrassing. Sure not all cities are perfect, and they all have their own unique and complex problems and histories, that’s not the point I want to make.

But look at Chicago’s downtown,

_ Image: _via “Let’s Go Somewhere New” -[youtube.com](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bzR_D0BZK2A)_](/assets/video/what-happened-to-downtown-atlanta/2Fe4d77a26-a38f-4e3c-ad24-7ad294e7d1c4_2580x1446.jpg)

via “Let’s Go Somewhere New” -youtube.com

or Seattle’s Pike Place Market,

_ Image: _via “Sound Wayz” -[youtube.com](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oMvPK9_BG40)_](/assets/video/what-happened-to-downtown-atlanta/2F741e0f99-6b70-473d-9f68-3f42caf9bac9_2580x1446.jpg)

via “Sound Wayz” -youtube.com

or even Savannah, Georgia.

_ Image: _via “Travel USA” -[youtube.com](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RjwdwLeb6pk) _](/assets/video/what-happened-to-downtown-atlanta/2Fc1fc7962-7f3a-4a63-848e-4a35ff3d6d0a_2580x1446.jpg)

_via “Travel USA” -youtube.com _

These places are vibrant, full of nightlife, and full of pedestrian activity.

They’ve got housing, shops, restaurants, bars, breweries, cafes, and much more all packed into these spaces. These places are places where people actually live, and spend time in. It’s a community even.

Fairlie-Poplar District, Downtown Atlanta

That’s not to say Atlanta doesn’t have these things in historic Downtown. The Fairlie-Poplar district is the best place to find this kind of thing.

Broad Street Boardwalk, Downtown Atlanta

Broad Street Boardwalk is frankly beautiful, and the historic core of small city blocks here makes it really enjoyable to walk around.

But Atlanta’s downtown on evenings and weekends is basically shut down, it’s like the city & businesses don't want it to be a destination, just a necessary evil.. The businesses here are simply responding to the reality: Locals don’t live here, and they make the most money serving the daytime hours of office workers, tourists, students, and suburbanites.

Initial thoughts

So why isn’t downtown Atlanta more like the more vibrant downtown’s of other American cities? Well, especially as someone who grew up in the suburbs, at first I thought this answer was pretty clear to me.

Downtown is generally just a place for tourists. As I said earlier, It’s the place you take your cousin to see the whale sharks, to run through the fountain, and spend a lot of money on the ferris wheel. Not a place to hangout, unless you've got a show at the tabernacle!

You know.. honestly, the more I think about it, the more I realize that Downtown's reputation to locals is more equivalent to a theme park than to a city’s downtown.

This lead me to realize once looking into it, I'm not the only person who's made this analogy. The real reason why Atlanta’s downtown sucks is a bit more political than you might think.

Cause and Effect

Suburbanification & White Flight

So where did everyone go? Well, I've talked about this before, but its primarily due to everyone moving to the suburbs.

See, people were pretty desperate to get out of cities. After the the Industrial Revolution, people wanted to get out of their polluted and noisy neighborhoods. And after World War 2, the popularity of the automobile, standardized building construction, and greenfield suburban development induced hundreds of thousands of people to chase this newfound American Dream.

Looking at population trends over the past several decades, we can really see how intensely the suburban and exurban counties of the Atlanta Metro Region have grown in comparison to the city of Atlanta.

_ Image: _Adapted from[Population Estimates for the Atlanta Region: Another Steady Year of Growth (2016)](http://www.documents.atlantaregional.com/snapshots/PopulationEstimates2016Snapshot.pdf)_](/assets/video/what-happened-to-downtown-atlanta/2F7bc30488-ce37-410a-a7c4-8e7caaf99b11_3840x2160.jpg)

Adapted fromPopulation Estimates for the Atlanta Region: Another Steady Year of Growth (2016)

This is commonly refereed to as white flight , due to mostly only white people having the means to leave the city economically, especially in the South. But as time went on, the black middle class also quickly left Atlanta as well, leading to a mass exodus of population from Atlanta proper to newly formed, suburban communities. The construction of the interstate system helped facilitate this too, allowing for easy travel to the city from these suburban enclaves.

_ Image: _American Suburb - Image from video by David McBee -[pexels.com](https://www.pexels.com/video/drone-footage-of-a-neighborhood-5031099/)_](/assets/video/what-happened-to-downtown-atlanta/2Fa60c04f1-a304-41dd-85b6-a0c7b8f93b9f_2404x1400.jpg)

American Suburb - Image from video by David McBee -pexels.com

Unfortunately, this has an immensely negative effect on urban areas of the time, and Atlanta suffered quite greatly. People needed road space to drive their cars, they needed parking to store their cars, and they especially needed a reason to drive into their city.

“Disneyification”, Modernist Architecture, John Portman

So, as the suburbs grew and grew, city leaders and developers began to think of how to serve these communities better. The old way of urban development was unpopular, and seemed like was no more.

After some further research, I began to read about the " Disneyification " of Downtown Atlanta, and how architecture of the time slowly but surely "modernized" the format of the city.

Architects of the time began to think of how to create this " New Downtown " of their dreams. And lucky for one man, he was given unrelented power over the second half of the century to do just that: John Portman.

via Google Earth

This infamous name is responsible for mega projects such as Peachtree Center, America's Mart, and the Marriot marquee. Famous for his large, stunning atrium, sprawling sky bridges that soared high above the streets, and cold, daunting constructions that kept the undesirables out, and the people within.

Projects such as these refactored the center of the city away from the historic center, Five Points, to this newly proclaimed " New Downtown " for the future. The problem was, these projects were absolutely horrible for street life, creating massive, uninviting walls of concrete,

loading bays,

and parking,

that made it downright hostile to be outside of his structures.

In Portman’s mind, one of the keys to an urban renaissance involves getting Americans out of their cars. So he structures his projects in accordance with something he refers to as a “coordinate unit,” the distance he believes a person will walk before climbing into “the four-wheeled monster.” Hence the sky-bridges, the clustering of white-collar labor and fun zones in his developments. (Arts ATL)

Not to mention, that block by block, property owners began to destroy nearby buildings for parking construction to service this audience, making the problem even worse.

These places were basically the equivalent of a suburban mall, designed to pull people into their climate controlled interiors, so they would never want to leave.

Perceptions

So clearly, this kind of architecture was taking over city blocks one by one, transforming formerly human scaled places to monotities of concrete.

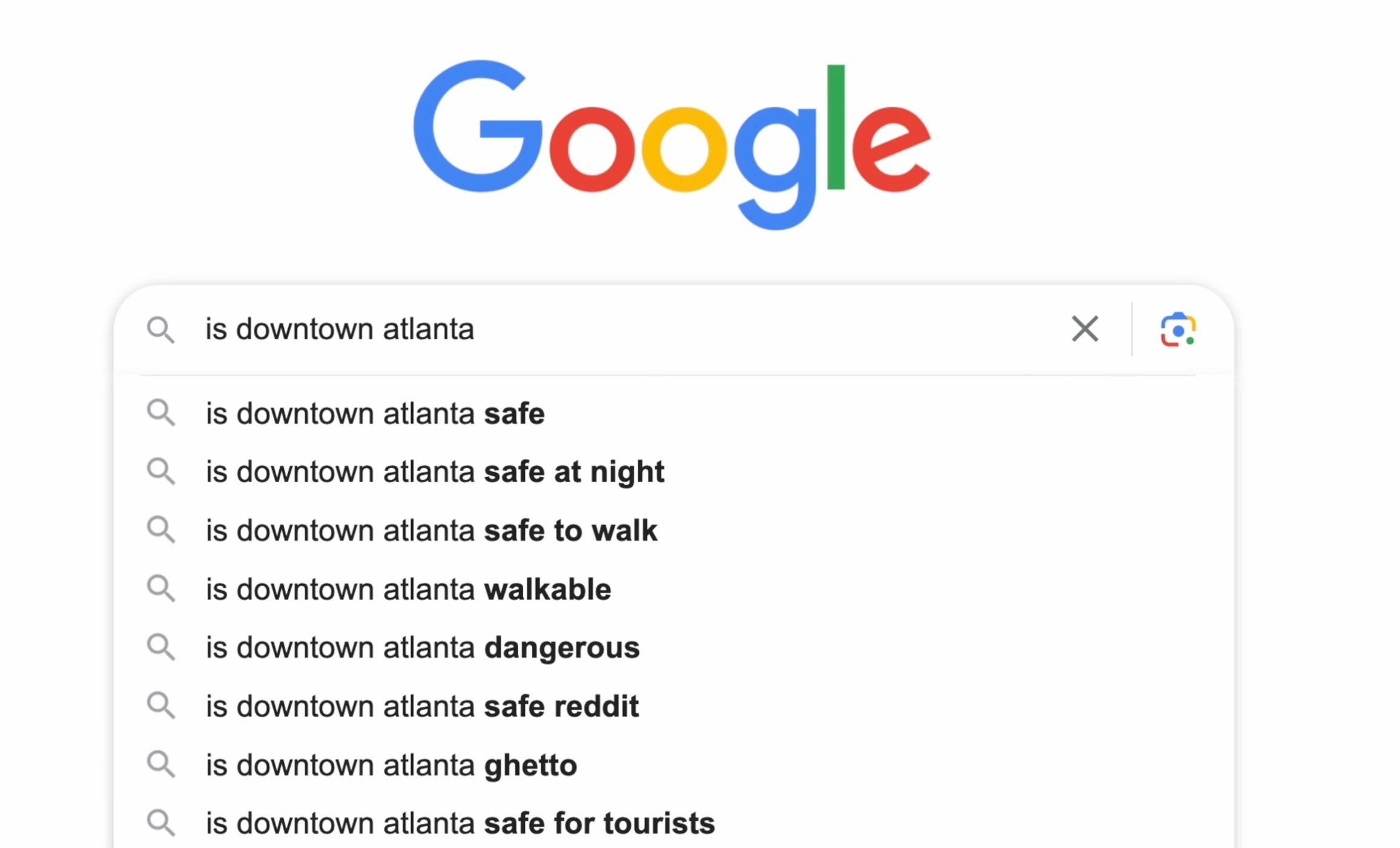

But the real reason for Downtown's weariness? well…. people thought its unsafe. You’ll get shot, you’ll get mugged, you’ll get your car broken into.

The more I read on this topic, the more I realized that this is only part of the very pervasive ideology tying this all together. And unfortunately, you can probably guess what it is.

Crime and Poverty

The most common thing people will tell you when you ask about downtown is safety — which more specifically, almost always means the homeless population. Decades and decades of systemic racism and disinvestment in our cities created a Downtown that, to this day, primarily exists to keep undesirable populations away from suburban enclaves outside the city.

To see how the city feels about this demographic of people in our city, look no further than the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games.

1996 Atlanta Olympic Games

The Olympics cemented this ideal. In 1992, Atlanta won it's bid for the International Olympic Games in 1996. This was a revelation for the city, and especially transformed Downtown in a short amount of time, for better or worse.

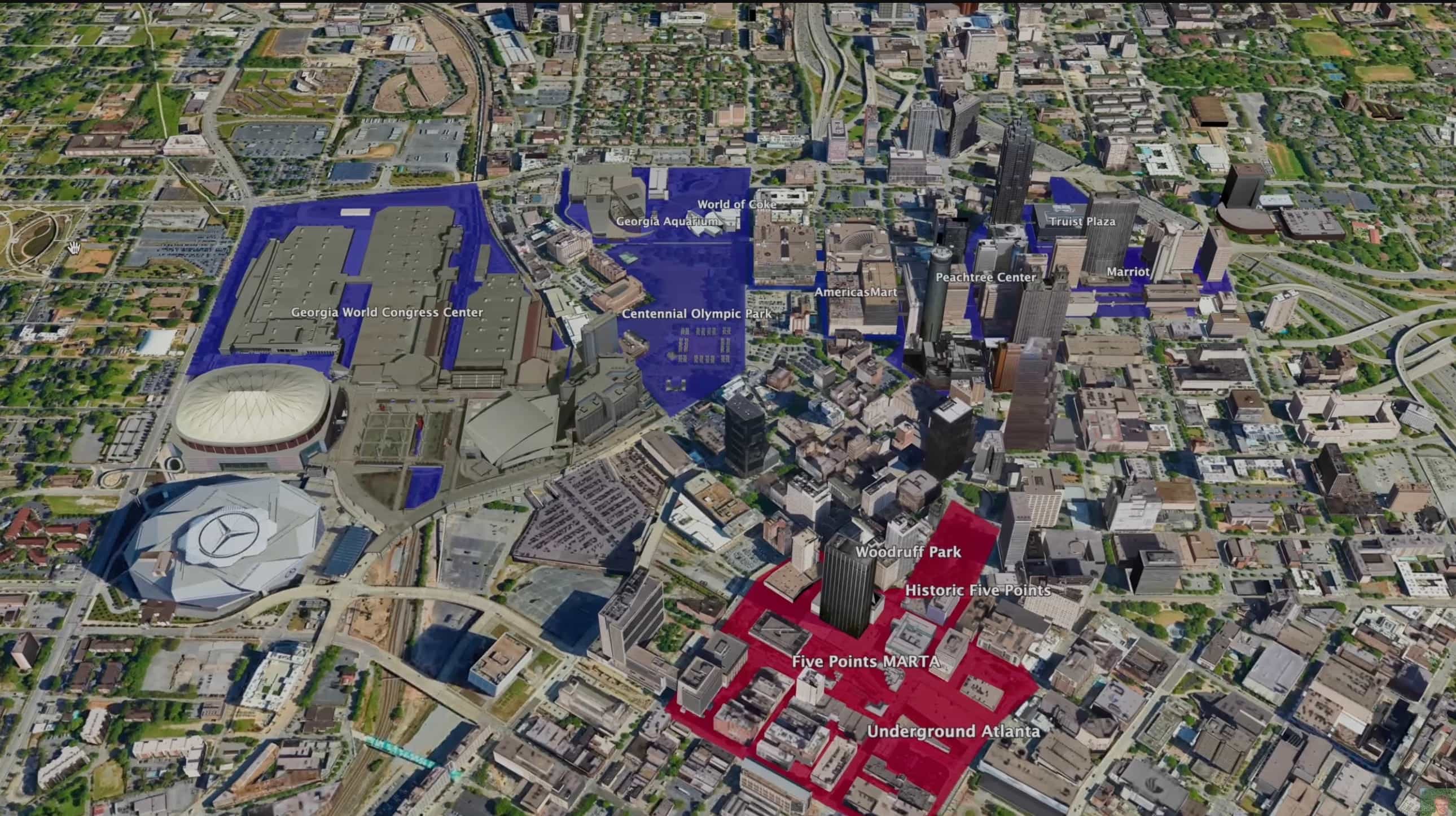

via Google Earth

The city began large construction projects, one of the most prominent being Centennial Olympic Park. This park spanned many city blocks, and created a massive new plaza in order to host the Olympics.

Centennial Olympic Park, Downtown Atlanta

The areas were formerly abandoned and industrial uses, but advocates at the time protested its construction since it slated one of the largest Atlanta homeless shelters to be destroyed. And, the beds in this shelter were never replaced.

Initial city plans hoped to revitalize many of the streets of Downtown, beautifying blocks, making pedestrian facilities safer, and more. However, what ended up happening was a so called “cooridor plan,” that strictly invested only in corridors between Olympic events and desirable destinations, for example, between Peachtree Center and Centennial Olympic Park.

Illustrating the Cooridor Plan, using Google Earth

And now for the fact that I find extremely astonishing. The city began to change its wording of people in the city — it began to use the terminology of “users.” No longer were people downtown residents or even people, they were simply “users” of the space, those that the city hoped would spend money in commercialized Downtown. This began to be reflected in signage across downtown, directing people through its defined corridors and areas of interest.

By the mid 1990s, even putatively liberal newspaper columnists blamed the homeless for almost single-handedly causing downtown's decline, conveniently overlooking the wider socioeconomic forces at play in motivating the corporate exodus from downtown. Rather than provide training, jobs, and housing for the homeless, both the city government and the business community are more interested in making downtown less amenable to these undesirable users. Actually, the homeless are not users at all, since users "use" the city by spending money. (via Theorizing The City: The New Urban Anthropology, 328)

So once the Olympics rolled in 1996, Fulton County quietly footed a one way bus ticket for thousands of homeless people in the Olympic areas. Additionally, they arrested over 9,000 people, cited just for looking either “homeless” or “African-American.”

On top of that, The city demolished the last of Atlanta’s public housing projects during this period: Techwood Homes and Clark Howell Homes, home to over 1600 families, forcing relocation of most far away from the area.

Image: Image by Eddie Richardson, via [medium.com](https://medium.com/@eddierich360/history-of-the-olympic-legacy-program-in-atlanta-georgia-44e47354a97b)](/assets/video/what-happened-to-downtown-atlanta/2F23799f5c-7cfc-40bd-a4ca-f768c210e65c_525x374.webp)

Image by Eddie Richardson, via medium.com

The Olympics transformed Downtown almost as quickly as the previous decades of suburbanization — they were staging a TV show, they made it look good for the cameras, but in the end, Downtown was changed forever.

Downtown Today

Well, did it work? I don’t know. I personally still enjoy downtown, theres a lot of places away from the commercialized areas that still have character.

The Downtown of today still suffers from many of the issues caused by the city’s previous decisions. One attempt to revitalize the area was with the Atlanta Streetcar in 2008, which promised to bring major redevelopment along its route, with housing and mixed uses. But uh, as you can probably predict, this was a major flop and was just became a glorified, unused tourist shuttle.

And, since COVID-19, Downtown has struggled to return to its pre pandemic activity levels. Many people are clearly working from home, and there is much less student activity due to online coursework. Many businesses have closed, and the ones that have stuck around have limited weekday hours.

Concluding Thoughts & Future Prospects

Now, I’m not gonna stand here and tell you that Downtown is a lost cause. I tell this story as a cautionary tale of both failure and success — that cities worldwide could learn from.

Ultimately, the best use of our urban spaces is what we make of it, and while Downtown Atlanta today feels heavily commercialized and inorganic, it doesn’t mean it isn’t a nice place to visit.

I’m personally hopeful for Downtown — I think now is an amazing opportunity for Downtown to redefine itself. It’s competing with other brand new, manicured areas of the city, like Midtown, The Eastside Beltline, and the Westside. But what Downtown has over these other place is history, character, and true human scaled walkability and the best transit connectivity of the region.

With future construction projects on the horizon, theres a real possibility of Downtown becoming the next hot thing.

Future Developments

For example, The Gulch, the massive array of road viaducts west of downtown, is seeing rapid development of high density residential and commercial spaces as of today.

The Gulch and Mercedes Benz, 2023

Centennial Yards will reconnect Castleberry Hill with South Downtown, and looks to be one of the best projects we’ve seen in the city in a long time.

The Eastside Streetcar Extension could bring thousands of new people into Downtown Atlanta via the streetcar.

Underground Atlanta is seeing another resurgence, with many new bars, clubs, and event spaces opening in its creepy underbelly.

Underground Atlanta, 2023

All in all, there’s a lot of hope for Downtown, and while many locals have craved a new resurgence for the district, it looks like there is promise on the horizon. (despite the recent foreclosure of Hotel Row redevelopment, via Urbanize Atlanta)

Concluding Thoughts

In cities across the world, the Downtown’s are what define and make a city what it is; culturally and economically.

At the end of the day, understanding the histories of our cities and spaces is the best way to push for greater; and I think we can push for better Downtown spaces, in Atlanta and across the globe, that everyone can love.

References

Primary Source

Low, Setha M. “The Anthropology of Cities: Imagining and Theorizing the City.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 25, 1996, pp. ~383 to ~409. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2155832. Accessed 23 Oct. 2023.

Free reference: https://archive.org/details/theorizingcityne0000unse/page/326

-

Theorizing the City: The New Urban Anthropology Reader. Edited by Setha M. Low and Neil Smith, Yale University Press, 1998, p. 326. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/theorizingcityne0000unse/page/362/mode/2up?view=theater.

-

"Atlanta's Population Growth: 1990-2020." Atlanta Regional Commission, n.d., https://33n.atlantaregional.com/data-diversions/atlantas-population-growth-1990-2020.

-

Oney, Steve. "10 Years of ArtsATL: How John Portman Changed Atlanta and Urban America." ArtsATL, 13 Mar. 2020, https://www.artsatl.org/10-years-of-artsatl-how-john-portman-changed-atlanta-and-urban-america/.

-

Theorizing the City: The New Urban Anthropology Reader. Edited by Setha M. Low and Neil Smith, Yale University Press, 1998, p. 328. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/theorizingcityne0000unse/page/328/mode/2up?view=theater.

-

AP. "Olympics -- Atlanta 'Cleanup' Includes One-Way Tickets For Homeless." Duluth News-Tribune, 22 Mar. 1996, https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=19960322&slug=2320280.

-

Kessler, Martin. "The Forgotten Story of Rio's First Favela and Its Connection to the Atlanta Olympics." Only A Game, 5 Aug. 2016, https://www.wbur.org/onlyagame/2016/08/05/autodromo-rio-atlanta-olympics.

-

Rogers, Katelynn. "Techwood Homes." History of Our Streets, 11 Apr. 2022, https://sites.gsu.edu/historyofourstreets/2022/04/11/techwood-homes/.

-

Nadeau, R. J. "The Abandoned Autódromo From Atlanta's Olympic Bid Still Stands In Rio." Only A Game, WBUR, 5 Aug. 2016, https://www.wbur.org/onlyagame/2016/08/05/autodromo-rio-atlanta-olympics.

-

Green, Josh. "Newport Selling South Downtown: All Buildings, Development Rights." Urbanize Atlanta, https://atlanta.urbanize.city/post/newport-selling-south-downtown-all-buildings-development.